|

The Untold of Guy Gabaldon

|

|

What motivated Gabaldon |

|

Somos Primos March 2006 |

|

The Untold of Guy Gabaldon

|

|

What motivated Gabaldon |

|

For more information,

please

Click

|

| Content Areas United States. . 4 Anti-Spanish Legends. . 26 Military Heroes and Research . . 32 Spanish Sons of the American Revolution. . 36 Surname. . 46 Cuentos. . 49 Orange County, CA. . 65 Los Angeles, CA. . 72 California. . 75 Northwestern United States. . 100 Southwestern United States. . 100 Black . . 112 Indigenous. . 122 |

Sephardic. . 131 Texas . 138 East of the Mississippi . . 157 East Coast . . 162 Mexico . . 165 Caribbean/Cuba . . 171 Spain . . 182 International. . 183 Family History . . 187 Archaeology. . 193 Calendar Networking Meetings, SHHAR Quarterly, March 11th END. . 196 |

|

Letters to the Editor : |

| § Hello Mimi. My name is Juan Vilaubí Monllaó and I'm writing you from Spain. Yesterday I found out by chance that a man called Juan Vilaubí Gisbert was born in California in 1895. He was the first Vilaubí registered in a US census, and having those surnames I'm 100 per cent sure his parents were from Tortosa, the place were I was born also. Vilaubí is not a very common surname over here. That's why I was greatly surprised to see that we have such a big family branch in America - afterwards I looked for more American relatives and I found 66 parientes. In case you know any of them: Una abraçada, cosins, i que tot vaigue molt bé! Esto último está escrito en catalán tortosí, la lengua materna de los Vilaubís, y quiere decir: "un abrazo, primos, y que todo vaya muy bien"). Muchas gracias, Juan Vilaubí Monllaó, ibualiv@hotmail.com, § Dear Ms. Lozano, I love your publication and would like to continue to receive it my E-mail address has changed. Will you please send this months newsletter and future newsletters to my new address. Hallaran2@msn.com thank you. M. Soto-Hallaran § Please delete aman156@juno.com and new e-mail address is jnbfarias@sbcglobal.net. The latest email copy of Somos Primos was Dec 05. My wife and I enjoy the articles published. A real awaking of our Texas/Hispanic history the schools don't teach. Keep up the good work . Thanks Jay, jnbfarias@sbcglobal.net § I continue to be amazed at your work on "Somos Primos". You are doing an absolute great work! Best, Carlos [Carlos Vega, Ph.D. Professor of Spanish, Iona College New Rochelle, New York is the Author of The Truth Must be Told ] § Thank for sending Somos Primos. I enjoying receiving and reading all the different articles. Finding ones Roots is so important, and your website sure helps. Gerri . . California researcher, gmares@san.rr.com § Hey Mimi!! I cannot even imagine how to be as comprehensive as your are doing with Somos Primos. It was for me an eye opener. It gives me insight of our movimineto en la NETA. The kind I had been missing and at the same time being unhappy thinking how our gente are missing the boat. How were you able to keep you FOCO so bright. fs fsconzafos@verizon.net |

§ WHAT YOU HAVE STARTED with SOMOS PRIMOS is priceless for its POTENTIAL. WHICH you are proving with the help of your troopers. Frank Kiko Sifuentes fsconzafos@verizon.net § Thank you. This is really great information on are Hispanic Heritage. I found more new family members through your column concerning my genealogy on Somos Primos. Thanks. Rosa Garcia West Sacramento California My new email address will be im1rose@yahoo.com § Mimi, Thank you so much for the opportunity to join Somos Primos. I have heard only good things about your organization and look forward to working together in tracing the Pacheco lineage. I'm hopeful other members might assist me in the brick walls I have run up against in researching my Grandfather Fernando Pacheco-born 1885 in Reventadero,Veracruz,Mexico to Domingo Pacheco and Fransisca(maiden name?) and my grandmother Maria Demetria Garcia-born 1896 in Silos,San Luis Potosi,Mexico to Juan Garcia and Balbina Plumarejo. I have been told by family members that a family member headed "west" when Fernando came to Texas. Not sure who that relative was. Fernando's siblings were Isac,Damian,Juan and Julia Pacheco. It is believed this relative settled in New Mexico. I have searched the New Mexico GenWeb with no luck so far, although there are a TON of Pacheco's with similar names(Domingo,Damian,Fernando etc.) I have even come across another Isaac James Pacheco. (note the extra "a" in Isac) I really appreciate any help I may receive. Thanks again, Mimi. Sincerely, Isac James Pacheco Jr. @ pmg4ike@lasercom.net § I read this month's Somos Primos from cover to cover. IT WAS GREAT. Also, thanks for printing our press release. The guys in Texas were thrilled. Again, muchas gracias. Later, Willie, gillermoperez@sbcglobal.net § I saw the Feb. issue of Somos Primos. Thanks for putting my story in there. I appreciate it. Richard Sanchez r-osunchase@msn.com |

|

Douglas Westfall,

|

|

Somos Primos Staff: Mimi Lozano, Editor Luke Holtzman, Assistant Reporters/columnists: Johanna De Soto Lila Guzman Granville Hough Galal Kernahan Alex Loya J.V. Martinez Armando Montes Michael Perez Ángel C. Rebollo John P. Schmal Howard Shorr Contributors: Soldelmar00@aol.com Marcy Bandy Maurice Bandy Mercy Bautista Olvera Alicia Burger Fred Blanco Eva Booher Bruce Buonauro Jaime Cader Bill Carmena Jack Cowan Gloria L. Cordova, Ph.D. Johanna De Soto |

George Farias Jay Farias Wade Falcon Lorraine Frain Guy Gabaldon Rosa Garcia George Gause Gloria Golden Mauricio J. González Sara Guerrero Lila Guzman, Ph.D. Diane Haddad Michael Hardwick, Manuel Hernandez Sergio Hernandez, Elsa Herbeck Sonya Herrera-Wilson Win Holtzman Granville Hough, Ph.D. John Inclan Mary-Ellen Jones Galal Kernahan Ignacio Koblischek Alex Loya Gerri Mares JV Martinez, Ph.D. Helen Mejia Z.-Savala Juan Vilaubí Monllaó Dorinda Moreno Paul Newfield III Isac James Pacheco Jr. |

Willis Papillion Willie Perez Dario Prieto Elvira Prieto Joseph Puentes Juan Ramos, Ph.D. Eduardo Ramos Garcia Angel Custodio Rebollo Frances Rios Ben Romero Pedro A. Romero Steve Rubin George Ryskamp Rubén Sálaz Richard Sanchez Gilbert Sandate, Ph.D. Diane Sears Howard Shorr M. Soto-Hallaran Carmen Moreno Sifuentes Shepard Frank "Kiko" Sifuentes Ivonne Urveta Thompson Paul Trejo Margarita Tapia Alfredo Valentin Janete Vargas Carlos G. Velez-Ibanez Carlos Vega, Ph.D. JD Villarreal Douglas Westfall Francisco Zamarripa, Ph.D |

| SHHAR Board: Laura Arechabala Shane, Bea Armenta Dever, Steven

Hernandez, Mimi Lozano Holtzman, Pat Lozano, Henry Marquez, Yolanda

Ochoa Hussey, Michael Perez, Crispin Rendon, Viola Rodriguez Sadler, John

P. Schmal |

| National

issues Focus on Veteran Rights For increasing Hispanic federal employment! Naval Academy Summer Seminar (NASS) Program Focus on Conversion of qualified Hispanic interns to federal employment! Developing Internal Policies for placing Interns in Federal Employment Library of Congress Jr Fellows Summer Intern Program, Deadline Mar 15 USDA International Internship > Seeks INTERNS, Deadline MAR 15, 2006 Smithsonian Internships > Spring Internship Fair, 26 April 2006 2/8 Notes: NHLA-Federal Government Under-representation of Hispanics Education Culture |

| National issues |

| Focus on Veteran Rights For increasing Hispanic federal employment! by Willis Papillion willis35@earthlink.net 1-Start a federal resume preparedness program, at their local churches-using the federal resume from OPM/Human Resource Dept. 2-Obtain copies of the federal civilian/military Helper and Apprenticeship test-from the federal book stores. And teach the youth how to pass these exams! 3-Also, get copies of the Postal exams. 4-Contact the VA and local military bases that are building ships and planes-to put you in touch with the Hispanics that are being discharge-to take advantage of their Veterans priority Vets. Preference, for the federal vacancies on their base! Match up the vacancies-with the recent dischargees, and college Vets. 5-Advise the Hispanic wife's of active duty military men-to enforce the Vets. Preference to the existing base federal vacancies! During my 36 year federal career-I learn that the surest way to increase the hiring of people of Color in the federal Gov. was through strict and continuing enforcement of Veterans preference in federal employment! Even with my Masters'-I still needed my veteran preference-to get my first federal job-in the seventies! During the seventies-we Blacks federal employees of the Office of Education, Region X, SF-along with our Hispanic brethren, gave federal job application training-on Saturdays-at the local Parks. And we provided them with all the news vacancies of: HUD, Dept. of Labor and Dept. of Education. What needs to be done is to contact their Regional Human Resource Office and that of all their local federal agencies-and start an outreach Community Hispanic Federal hiring program. And have these federal agencies provide them with the updated federal vacancies! Also, it should be noted: majority of the military bases-have a continuing free educational program and advancement. Most importantly, the military-especially the Navy and Air Force, has always operated a revolving door policy for it's military people-to federal civilian positions and DOD contracts and hiring-not necessarily Equal Opportunity hiring! Additionally, there are three major Naval Bases, in our Kitsap County: Bangor Subase, Keyport and Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, And the Naval Commanders-are constituency telling me at the Navy League meetings-that they're extremely low in representation of Hispanic and Black-Engineers and Electronic Techs. We need the National Hispanic Engineers Society-to talk to their students-to re-locate out here! The Navy active duty and federal civilians-will always remain a: Old Boy White Man's Country Club. Until we aggressively break it up! And last but not lease-is the Navy League magazine and American Legion magazine, which I've been receiving for the last ten years. Never an article on Hispanic military fighting men and/or heroes-public sentiment is everything! Also, contact ANSO, an active duty Hispanic Officer organization-which help me very much in recruiting Hispanic officers-when I was in charge of Naval Educational programs, in Northern Calif. All of these recommendations will not become a reality -with out commands from the top, and continuing media pressure-especial during an election year. Willis Papillion

|

| Naval Academy Summer Seminar

(NASS) Program Sent by Willis Papillion: willis35@earthlink.net On February 1, 2006, the United States Naval Academy will open online for current juniors (current high school class of 2007) to apply for the Naval Academy Summer Seminar (NASS) Program. A series of 6-day immersion programs, running the first three weeks of June in three sessions (Sessions I - 6/3 to 6/8, II 6/10 to 6/15, III - 6/17 to 6/22). Participating in each session will be 600 of the nations top rising seniors. Online application: http://www.usna.edu/Admissions/nass.htm |

| Focus on Interns:

Promotion

of Hispanic interns to federal employment October 17, 2005 Excerpt from a MEMORANDUM by Dario Prieto, DPrieto@hrsa.gov Hispanic Employment Manager, Office of Equal Opportunity and Civil Rights, Health Resources and Services Administration TO: National Hispanic Employment Initiative Work Group SUBJECT: Hispanic Employment in DHHS A number of documents generated from the DHHS Office of the Secretary, Presidential Executive Orders, OPM, and news paper articles have all surfaced in the last few years, as a result and recognition that Hispanic Americans remain the only underrepresented group within the DHHS. With the exception of National Hispanic Employment Initiative initiated by Secretary Leavitt, (because it is too early to tell), none of these initiatives have resulted in any significant increase in the number of Hispanics among the DHHS employees. For many of these initiatives, the focus of hiring has been on diversity rather than on Hispanics alone thus allowing managers and supervisors to increase hiring of diverse and ethnic minority groups while Hispanics remain the only underrepresented group. As Hispanic Employment manager, over the years, I have submitted resumes of outstanding Hispanic candidates (M.D. Ph.D. R.N., M.P.H. and J.D. types, etc.) for various positions but due to the limitations of hiring authorities and lack of commitment to hire Hispanics by managers and supervisors, almost none were hired. Each year over the last 8 years, I have worked with the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU) to recruit HACU interns (mostly graduates from schools of public health) to work for the summer and although many of them have indicated an interest in staying to work permanently for our agency, only a couple have been able to remain, primarily because they joined the Commission Corp. Again, there are no hiring authorities that would allow the conversion of qualified Hispanic interns to regular employment. By contrast, there are federal programs such as the Presidential Management Internship (which recruits very few Hispanics) that allows the conversion of interns to regular employment upon completion of the internship. I have also been aware of agency agreements with some universities where they take interns and convert them to regular employment once the internship is completed (unfortunately, these programs have lacked adequate Hispanic representation) and most of the hiring is done by individual managers and supervisors who are unaware of Hispanic underrepresentation. Even programs such as the DHHS Emerging Leaders which is partially designed to hire talented college graduates to replace an aging DHHS workforce in the near future has not recruited Hispanics aggressively and therefore Hispanics are very underrepresented among those that have been recruited. HACU has a data base of literally thousands of Hispanic college graduates and undergraduates from over 160 institutions of higher learning with outstanding qualifications. Hundreds of them have worked as summer interns for federal agencies in metropolitan Washington and other federal agencies such as CDC in Atlanta and Texas. This program is an ideal vehicle for the recruitment of Hispanics into DHHS if only a hiring authority would be developed to convert these highly qualified interns into full-time employees. Some agencies have taken steps to move in this direction. USDA for example, has hosted 439 HACU interns since 2001. Of these interns, 21% (92 interns) were converted or hired as permanent employees by USDA. With this information as background, as a Hispanic Employment Manager, I submit the following recommendations for your consideration as you deliberate ways to improve the under representation of Hispanic Americans within the DHHS workforce. My recommendations focus on the three areas of: Recruitment, Retention, and Management Accountability. [[ The full 6 page report by Dario Prieto has been sent to LULAC, La Raza, and the Puerto Rican Coalition. ]]

|

| Developing

Internal Policies for placing Interns in Federal Employment Please be advised that some agencies, including the Library of Congress, have taken the initiative of developing their own internal appointment policies whereby HACU interns can be hired non-competitively upon successful completion of their internships. These internal policies, tailored to meet the agencies' unique needs, must be vetted and approved by OPM before they can be implemented. The Library's HACU-Cooperative Education Program allows for the non-competitive conversion of HACU interns who have successfully completed a minimum of 640 hours of career-related work at the Library. HACU-COOP interns may be appointed to permanent-conditional positions for which they qualify within one year of completing their academic degree requirements. Sinceramente, Gilbert Sandate Director, Office of Workforce Diversity, Library of Congress

|

|

| Library

of Congress Jr

Fellows Summer Intern Program, Deadline

March 15

The Library of Congress' Junior Fellows' Summer Intern program offers undergraduate and graduate students insights into the environment and culture of the world's largest and most comprehensive repository of human knowledge. Working with the staff, curators, and the incomparable collections of the Library of Congress, interns will be exposed to a broad spectrum of library work: preservation, reference, access standards, information management, and the U. S. copyright system. No previous experience is necessary, but internships are competitive

and special relevant skills are desirable. Selection will be based on

academic achievement, letters of recommendation, and in most cases an

interview with a selection official. Please

act quickly: http://www.loc.gov/hr/jrfellows/

|

| USDA International Internship Program

PLEASE Circulate!! The USDA Foreign Agricultural Service's International Internship Program is a PAID internship program and is in need of applicants! Deadline March 15. Sent by Juan Ramos jramos.swkr@comcast.net Spend a summer working in a U.S. Embassy in one of 90 locations throughout the world! As of this week, the program has only received 3 applications nationwide! Due to this low number of applications the deadline has been extended to March 15. The Foreign Agricultural Service's International Internship Program provides college students the opportunity to live and work in a paid internship at an American Embassy overseas. Through work assignments participants learn various aspects of international trade, trade policy, international relations, diplomacy, regional and cultural considerations, etc. Positions are available in Western Europe, Latin America, and Asia. The internship is offered every semester and summer for graduate students and upperclassmen (juniors and seniors). Requirements: Be a currently enrolled graduate or undergraduate student (must be a junior or a senior), a U.S. citizen and in good academic standing. Graduate level students in business, international relations, regional studies (i.e. Latin American Studies, Asian Studies, etc), public policy, foreign languages, etc., as well as high-achieving junior and senior undergraduates in similar majors are particularly encouraged to apply, though the program is open to all majors. Please see the application at the website below. HYPERLINK http://www.fas.usda.gov/admin/student

This internship program is a great way to get international experience and expose yourself to career fields you may never have considered.

Please do not let any part of the application intimidate you! If you need help, that's my job to help you. It is completely doable! Also, the application states that you must pay for your own transportation to your job site. If that is a financial problem, still apply and we'll see how we can find you financial assistance. |

|

Internships

at the Smithsonian

|

|

NHLA-Federal Government Under-representation of Hispanics Notes of meeting held on – Feb 8, 2006, sent by Gilbert Sandate, gsandate@loc.gov Meeting convened by LULAC, NPRC, and ASPIRA to address in a more concerted manner the issue of under-representation of Hispanics in the federal government. The NHLA Chair, Ronald Blackburn Moreno, made a commitment to work on this issue and to begin addressing it on a more consistent basis, making it a major initiative over the next few years. Over 40 attendees,

representing Federal agencies as well as Hispanic advocacy organizations,

discussed ideas for addressing the problem of Hispanic

under-representation in the Federal workforce. The discussion focused on

setting a strategic plan of action under the NHLA banner that all could

endorse, support and implement. The goal is to have a strategic plan that

all organizations and Federal employees can support and help implement.

Key points include the following: Communication Strategy Research and Assessments

Strategy Infrastructure Assignments: 2. Prepare Media Strategy and Press Conference on GAO – Manny Mirabal3. Meet with Agencies & Conduct Letter Writing Campaign - Ron Blackburn Moreno4. Create Legislative Strategy: Senate/House Government Reform Committee Hearings – Brent Wilkes, Emma Moreno, and Gabriela D. Lemus5. Define Accountability Issues for Legislation- Organize structure at the White House and Agencies - Tie accountability to SES Bonus System - Tie accountability to budget 6. Create Commission/Review Board of Federal Experts- Conduct education/outreach effort - Hold seminars on importance of diversity in workplace - Hold seminars on Federal HR processes - Hold Federal career events for young Hispanics - Hold seminars on the Federal application and hiring process - Develop database of Federal experts – Harry Salinas 7. Report Card: Federal Service – NHLA8. Gather Intelligence - NAHFE- Identify barriers specific to agencies, i.e., OGC, etc.

|

| Education | |

| Cesar Chavez

& Bernardo de Galvez

Cesar Chavez's birthday on March 31st. is being honored by Fred Blanco in a new production, Cesar Chavez y Bernardo de Galvez: Sons and Souls of California. Fred Blanco and Bruce Buonauro, both being educational performers, produced shows individually, predominately for educational venues, such as schools and libraries. They both had an interest in telling Chavez and Galvez' stories. They decided to widen their audience and create versions that contained enough depth to engage older audiences . The production explores the humanity of these two men revealing to the audience, two people, as opposed to just two historical figures. Click for more information. |

|

|

Successful marriages are conferring a remarkable academic benefit on children Source: secretariat@worldcongress.org 1/30/2006

A new study published in the Journal of Divorce & Remarriage clearly shows that parents who make their marriage successful are conferring a remarkable academic benefit on their children - especially their daughters. | |

|

Hispanic advocates sue Texas over ESL and bilingual programs, AP, 2-9-06 Sent by JD Villarreal juandv@granderiver.net Latino advocates filed a federal lawsuit Thursday asking that Texas improve supervision over English as a Second Language and bilingual education programs to ensure students who are learning English don't lag behind others. The lawsuit contends Texas has failed for years to appropriately oversee the programs at public schools, leaving thousands of children with limited English skills to fail exit tests, drop out or be held back. Filed by Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the Multicultural Training, Education and Advocacy, Inc., the lawsuit requests that the Texas Education Agency be ordered to establish a system to monitor students who are learning English. It asks for the agency to monitor bilingual and ESL programs on-site, ensure access for students and make sure the instruction offered is appropriate. The lawsuit, filed on behalf of the League of United Latin American Citizens and the American GI Forum, also wants intervention for schools where the achievement gap, retention rate and drop out figures of students learning English is significant. Following a previous lawsuit, the district court in 1981 found inadequacies in the state's bilingual program that were made worse by the state's failure to monitor and enforce local compliance. An appeals court later said the program was unsound, largely unimplemented and yielded unproductive results. A spokeswoman for the Texas Education Agency said Thursday night that officials were in a board meeting and she didn't know if anyone had seen the lawsuit. | |

|

Yahoo discussion Groups Puerto Rican teacher Manuel Hernandez created a Yahoo group for the discussion of literature and education. HispanicVista highly recommends this effort and urges its readers to join and participate.

mannyh32@yahoo.com or visit and join at:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/latinoliterature | |

|

WALKOUT Screening in Austin - March 1, 2006 Sent by vira@mail.utexas.edu NALIP-Austin with Cine las Americas present a free, sneak-peek of the HBO film, Walkout Wednesday, March 1 at 8:00 pm at Ruta Maya Coffee House, 3601 South Congress Avenue. By special arrangement with Maya Pictures Directed by Edward James Olmos (American Me) Produced by Moctesuma Esparza (Selena, Introducing Dorothy Dandridge) Silent auction benefiting NALIP-Austin precedes the screening featuring movie posters, DVD sets and other film-fan goodies. Silent Auction: 6:30 to 8:00pm. Screening of WALKOUT: 8-10 pm. Based on actual events, the HBO film tells the story of a Chicano student uprising in 1968 when 12 students organized a peaceful demonstration (a walkout) to call attention to the substandard conditions of their East Los Angeles High school, and ultimately, the systemic discrimination that supported those inadequacies. Students from all five Eastside high schools participated in the peaceful demonstration — many, against their concerned parents wishes. But when the second day of the peaceful protest turned violent, the parents joined their children in what becomes a defining moment in Chicano civil rights history. Directed by Edward James Olmos, Walkout stars Michael Peña (Crash), Alexa Vega (Spy Kids), Bodie Olmos and Yancey Arias (Mi Familia). In addition to directing, Olmos has a supporting role. Austin audiences can see the film movie prior to it’s March 18 HBO premiere. A silent auction benefiting NALIP-Austin occurs prior to the screening at 6:30pm. NALIP-Austin is an approved chapter of the National Association of Latino Independent Producers, a non-profit organization. For more information call (512) 589-7076 or go to www.nalip-austin.org. WALKOUT is based on real events that occurred in 1968. Michael Peña (Crash, Million Dollar Baby) stars as Sal Castro, a dedicated teacher at Lincoln High School in East Los Angeles. Driven and determined that his mostly Mexican American students learn their cultural history — non-existent in their textbooks — he takes a group of his students to the Chicano Youth Leadership Conference. There, his and hundreds of students from across the state, learn about their collective history and what it means to claim their heritage. Castro’s brightest students — Paula Crisostomo (Alexa Vega), Yoli (Veronica Diaz) and Bobby Verdugo (Efren Ramirez) — return from the conference inspired and no longer willing to ignore the inequitable and often draconian conditions of their school — no bathroom breaks during lunch, forbidding Spanish from on school grounds. Although parents and even Peña himself begins to worry about the students’ newfound activism, in the end, all come to realize the simplicity and gravity of their demand: that their education be equitable, that their history be taught, and that self-respect is not a luxury. “I think this film will help inspire kids,” Director Edward James Olmos says in press materials. “I think they’re going to learn from the experience that these students were trying to understand: self respect, self-esteem and self worth is the single most important aspect of living. It’s what makes you and gives you the ability to say to yourself, ‘I want to move forward to be the best (I) can be.’” Executive Producer Moctesuma Esparza was a key participant in the real-life drama (as portrayed by Bodie Olmos, son of Edward James Olmos). In addition to Esparza’s Maya Pictures producing Walkout, he is a board member of the National Association of Latino Independent Producers. NALIP-Austin became an approved chapter in 2005. About NALIP and NALIP-Austin: The National Association of Latino Independent Producers (NALIP) is a national membership organization that addresses the professional needs of Latino/Latina independent producers. Founding in 1999, NALIP has since held five national Conferences, developed local chapters, and hosted many regional workshops and networking events that develop the professional skills of film, television, documentary and new media makers. In 2003, three new National Initiatives were launched: a Latino Writer's Lab, a Latino Producers Academy and a Latino Media Resource Guide published in print and online. NALIP's mission is to promote the advancement, development and funding of Latino/Latina film and media arts in all genres. NALIP is the only national organization committed to supporting both grassroots and community-based producers/media makers along with publicly funded and industry-based producers. As an approved chapter, NALIP-Austin follows the mission of the parent organization on a local level. For more info about NALIP, visit www.nalip.org . For more information on NALIP-Austin visit www.nalip-austin.org. About Cine las Americas: Now entering its 9th year, the Cine las Americas International Film Festival provides Central Texas with a diversity of Latino and indigenous film and media entertainment from across the Americas. Cine las A ericas’ education programs enables young filmmakers and musicians who might not otherwise have the opportunity to explore their artistic talents in a constructive atmosphere. The 9th Annual Cine las Americas Film Festival takes place April 19 – 23, 2006. For more information about the festival and other Cine las Americas programs visit www.cinelasamericas.org. For more within this issue of Somos Primos article on Sal

Castro . . . Click

|

| Octavio

Gomez, 71 Cover Latino Civil Rights Movement By VALBBIBJ. NELSON- Times Staff Writer Octavio Gomez, a cameraman, whose work put him at the center of the region's Mexican American civil rights movement and placed him by Ruben Salazar's side when the journalist was killed while covering a riot in 1970, has died. He was 71. Gomez, one of the first Latinos to work locally as a television camera-man, died of a heart attack Dec. 30 at a friend's home in Los Angeles. "He was a true pioneer of Hispanic media here in Los Angeles," said Frank Cruz, a former television news anchor and a founder of the Spanish-language network Telemundo. "And he was a gutsy cameraman." Felix Gutierrez, a USC Journalism professor, Called Gomez a "break-through journalist" because he suc-ceeded in the print and broadcasting media, "which very few have done." Shortly after arriving in Los An-geles in 1969, Gomez became a cameraman at the Spanish- language statlon KMEX. Later, he spent several years as a photographer at the Spanish-language newspaper La Opinion and freelanced for many broadcast out-lets. "He would stop at no end to get a story, including flying off to Central America with KMEX-TV camera equipment without getting his bosses' permission," Gutterrez re-called. In 1985, Gomez was awarded $195,000 in damages in a press freedom case that accused immigration authorities of interfering with his ability to take photographs for La Opinion. The lawsuit centered on two events a week apart — a protest against refugee deportations and a roundup of Illegal aliens — in which INS agents confiscated Gomez's camera and press credentials and reportedly made veiled threats about his immigration status. At the time, Gomez was a Mexican national who had been in the country legally since 1968. He became a naturalized citizen in 1994. "It wasn’t that trouble followed him, It's that he was fearless," said his elder son, Michael, who witnessed the second Incident as a 12-year-old riding along with his father in 1981. "Being an immigrant, he was pretty sympathetic to the cause." |

| Culture | |

| Excerpt

from: OC Register Dec 2, 2005 Latino TV characters seen as the hot gift By Cindy Kirscher Goodman Clearly, retailers want to tap into the increasingly strong Hispanic buying power. Hispanics spend twice the amount of money on kids products as other Americans do. "Hispanics are a strong target market," said Jonathan Breiter, senior vice president of Toy Play, which holds licenses for 25 "Dora the Explorer" products. Hispanics tend to outspend the rest of the nation in some categories such as children's clothing, said economist Jeffrey Humphreys. Moreover, a large percentage of the His-panic population is young. But. there is more: With Dora leading the way, these popular characters are reaching beyond their original niche audiences. Surprising even the show's creator, Dora ranks as the most recognizable 7-year-old in the world, with estimated reran sales of tier merchandise at a staggering $3 billion. |

|

|

"Maya & Miguel," an animated series created by Scholastic for PBS, is gaining ground. The show about the adventures of 10-year-old twins, their abuela or grandmother, bilingual parrot and diverse neighborhood, launched its second season this fall. Already, it attracts more than 4 million kids a week and ranks in the top 10 programs for children age 6 to 8. In February, PBS kicked off the third season of its popular "Dragon Tales" with a new Hispanic character, Enrique. Even Disney is getting in on the act. In 2006, Disney Channel will launch its new animated series "Handy Manny" about a Latino hero and his talking tools. |

| Finding Words to Talk About Race By Maria Luisa Tucker, AlterNet. Posted January 16, 2006. Sent by Howard Shorr howardshorr@msn.com I am the daughter of an Ecuadorian immigrant mother and a father from a Southern white ranching family. I was born in East Texas, in a town where people frequently called my mom "wetback" and "taco-bender" to her face. In an attempt to protect her children from this verbal brutality, my mother did not teach us to speak Spanish. She wanted us to quietly blend in, to be as unnoticeable as possible. When I was 2, we moved to a more quietly intolerant college town in the central part of the state, where black, white and brown were equally fractioned. My brother and I were assumed by most to either be plain ol' white or part Chicano. In middle school, a fellow classmate spit the word "Mexican" at me as if it were an insult, and so I took it as one. In high school, I had one ear listening to Selena, the other tuned to Kurt Cobain. I had no language to talk about these divides of difference. "Race" meant white or black. "Ethnicity" meant ... well, most people weren't exactly sure what it meant, but ethnic food was anything spicy, and ethnic clothes were folksy costumes. To actually discuss prejudice or discrimination, its causes and consequences and daily realities — that was as distasteful as talking about sex at the dinner table. Even when James Byrd, Jr., was murdered in Jasper, Texas -- he was chained by his ankles and dragged behind a pickup truck -- and the murderers were tried and convicted in my hometown, people didn't talk about it. And there, right in the center of middle class, middle America, is the root of this nation's difficulty in talking about race and ethnicity. My mother's generation was bullied into fitting in. In a post-civil rights world, my generation grew up obeying a polite colorblindness, a denial of difference. For decades, we quietly ignored race, which meant we ignored discrimination, and we shrank from talking about racial or ethnic tensions. Today, primarily because of Hurricane Katrina, Americans have finally acknowledged that, actually, we do have to talk about race. We're just having trouble finding the right words. What's needed are a million personal conversations between ordinary Americans. The complexities and nuances of color and culture, the disparities of wealth and education are best understood by learning the stories of each others' lives. Ordinary people are the true experts in cross-racial, cross-ethnic dialogue, if only we would start talking. Whenever I begin to be lulled into the tranquil idea that maybe, just maybe, race and ethnicity don't matter, something happens to remind me of the power of these things to be either connecters or dividers. A couple years ago, I was working on an article about the families of murder victims and had been invited to attend a support group for grieving parents. At the end of the meeting, I sat quietly reading some of the group's materials. An old Mexican man came up to me and asked, "Your name is Maria Luisa? Are you Hispanic?" This man's son had recently been murdered. He looked into my eyes -- he, the subject, me, the reporter -- and tried to decide whether to trust me with his story of grief. "Yes, but my father is white," I answered. "Well," he said, pausing to touch my pale hand. "Make sure to tell people your name is Maria." Then, he began his story. He didn't want to know my credentials as a journalist, only my ethnicity. He told me about the agony of watching his crack-addicted son go down a dangerous path. He told me about the miserable end to a three-day search, when his son's lifeless body was found in a dumpster. He spilled family secrets because he assumed that since we were both Latino, we shared the same values. It is significant that a name, skin tone or accent has so much emotional hold over us. Had my name been Amanda or Tiffany, the old man may never have greeted me. Actually, my name is different, and is pronounced differently, depending on who I'm talking to. Friends and family call me Luisa. When asked why I use only one half of my first name, I explain that most women in my extended family are named Maria something-or-other, so we Marias go by nicknames or shortened versions of our full names. I'm not sure if this is entirely true, but most of the non-Latino people I meet demand an explanation, so I made one up for them. When I introduce myself to Latino folks, I am Maria Luisa, the namesake of my maternal great-grandmother and the most obvious symbol of my Hispanic heritage. Like reminiscing about biscuits and gravy with fellow Southerners, most of the time I consider this variation on my introduction as a way to connect with Latinos. But sometimes, I feel like I'm pimping out my pseudo-Hispanic identity, like wearing a low-cut blouse in an attempt to get a special discount. Am I a cultural con artist, a disingenuous fake? What does it really mean to be Hispanic, if my skin is white and my language is English? Throughout my teens, I wondered about this. I hesitated to identify myself as a minority. I didn't feel like a "minority," nor did I know what that was supposed to feel like. But when I filled out forms for financial aid and college scholarships, being a minority took on a positive connotation. "Different" morphed into "diverse." The mother who had refused to teach us Spanish as children encouraged us to make sure we checked the "Hispanic" designation as college students. In college, I dabbled in trying to feel like a minority. I went to a Hispanic sorority party. I briefly joined an organization promoting racial equality. I attended a church group that promoted interracial marriage and ending racism as a spiritual goal. Openly talking about race puts us at risk of being sucked into a quicksand of accusations and defensive anger. We fear the reactions to our words, cringe at the thought of being labeled. Depending on which side of the color line we stand on, we are afraid to offend, or we're afraid to be singled out. We don't want to be forced to act as a representative for all people of color or be questioned about the authenticity of belonging to a certain tribe. And what words should we use when we do talk about race? Blacks may be unsure whether they should say "Latino" or "Hispanic." Whites may not know if it's PC to talk about Ebonics. A Christian once advised me not to call Jewish people "Jews" because, he said, the word was an epithet. And so conversations are stopped before they even begin. The discomfort that goes hand in hand with discussions about race has halted conversations within my own bi-ethnic family. My parents divorced long ago. My father remarried, to a woman who was both white and blonde. They wanted more children, but were unable to conceive. Finally, two years ago, they adopted three Mexican-American siblings who had been in foster care. My left-leaning, hippie-esque father and I have never once had a conversation about race or ethnicity; the adoption of three little brown children didn't change that sad fact. Secretly, I was thrilled at the addition of more Latin blood into the family. I daydreamed of bonding over our shared ethnicity. I would watch Dora the Explorer with them and show them how to dance the meringue. Like the old Mexican man, I assumed we would share similar values and interests because we shared a Latin American heritage. My fantasies were halted when my father announced that, at the adoption ceremony, their names would be changed. Their "Mexican-sounding" names would be simplified into shorter, "white" names. Ostensibly, this was a protective measure to prevent the children from being teased. I wanted to scream at my dad; I felt this was a mistake worse than my mom abandoning Spanish. It was denying more than language -- it was denying their very identities. These three sweet-natured brown-eyed, brown-skinned children were being raised in a state that was about one-third Hispanic, yet their new parents' first lesson was that being Latino was strange and should be hidden. I couldn't understand why my father would do this. Two months ago, I got my answer. After years of poor health, my dad's mother passed away. After the funeral, I caught up with my paternal relatives, who I hadn't seen in years. My mother had kept her distance from them during my childhood, and I had been repeatedly warned to stay away from one particular uncle. (Later I learned he was one of the individuals who referred to my mom as a "wetback.") It was this uncle who approached me. "You know, your dad's problems started with those kids," he said. I was silent. "Those Mexican kids, you know. I told him he needed to change their names. It's just a fact of life that old white guys like me will mess with them." He was apparently oblivious that he was talking to his niece, Maria Luisa. He might as well have said my father's problems started with my mother, or with me. What he did say was, "The world is full of old white guys like me." It took a minute for the meaning of his words to sink in. By the time I found my tongue again, he was gone. My uncle is right. There are a lot of old white guys like him. The world is full of people who unthinkingly buy into racism and prejudice. And the world is full of people who are afraid of those white guys and afraid of talking about the jumbled mess of race and racism. Because talking about our prejudices, our color, our deeply felt experiences, means exposing ourselves and our families. Conversations about race and ethnicity are conversations about sex, hate, love, ignorance, history, guilt, shame and anger. It's embarrassing, uncomfortable and emotionally draining. Given the choice, we'd rather not talk about it. But given the state of things, we should try. |

| Sibling Writing Team Surprises Again Susan & Denise Abraham The sister act of Susan and Denise Gonzales Abraham made a big impression with their debut novel in 2004, Cecilia’s Year. In a strong year for YA fiction, their novel beat out the competition for the Texas Institute of Letters Prize for that category. Surprising Cecilia, the second in a planned series about the title character Cecilia, keeps the momentum from their first novel rolling. Surprising Cecilia is an engaging, tender-hearted story of a girl becoming a young woman. The best part of it all is that the story comes from a Latino cultural background that until the last few years has been under-represented in the pantheon of young adult literature. Bravo sisters! Click here to buy books: Cecilia’s Year (Winner of the Texas Institute of Letters Best YA Book)—an historical novel set in the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico just after the Great Depression. The novel’s title character struggles to balance the demands of life on her family’s farm with her ambitions of education and a life in the big cities she reads about in magazines and novels. Deeply rooted in the culture and traditions of the American Southwest, Cecilia’s Year is also strongly reminiscent of YA classics like Anne of Green Gables and Little House on the Prairie. Click here to buy books: Susan and Denise Gonzales Abraham are the daughters of Cecilia Gonzales Abraham, the title character of Cecilia’s Year and Surprising Cecilia. The sisters were born and raised in El Paso, Texas, but spent holidays and every summer on their grandparents’ farm in Derry, New Mexico. They both graduated from the University of Texas at El Paso with a B.S. in Education. The authors are currently working on the third novel in the Cecilia Series. They enjoy presenting their books at schools and readings. Click here to view teacher's guide: Cinco Puntos Press, 701 Texas Ave., El Paso, Texas 79901 Phone: (915) 838-1625 Fax: (915) 838-1635 www.cincopuntos.com |

"La Tragedia de Macario." Excerpt: Prestigious festival accepts San Antonio filmmaker's maiden effort Elda Silva, lsilva@express-news.net San Antonio Express-News Sent by JV Martinez "La Tragedia de Macario," film by Pablo Véliz, a communications major at the University of Texas at San Antonio, was selected to have its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. Shot in San Antonio over eight days with a budget of $7,000, "La Tragedia de Macario" tells a story close to Véliz's heart - that of a young Mexican immigrant who attempts to cross the border illegally into the United States. In search of a better life, the title character contracts with a coyote who promises safe passage in a railroad boxcar. He finds misfortune instead. The movie, in Spanish with English subtitles, is based on the true story of 19 illegal immigrants who died inside a locked tractor-trailer in Victoria in May 2003. The story is set in Sabinas Hidalgo, Nuevo Leon, Mexico.

"Los Tigres del Norte are a huge inspiration in my filmmaking," Véliz says. "They're my No. 1 inspiration, above filmmakers, because they tell the inspiring stories. In songs they tell them in about three minutes. I tell them in about 90 minutes." | ||

Nuestra Familia Unida podcast project From: makas@nc.rr.com http://NuestraFamiliaUnida.com The Nuestra Familia Unida podcast* project needs your help. [*podcasting is putting audio files on the internet]. This effort is an attempt to archive as much audio related to our history as possible. Have a look at the website - http://NuestraFamiliaUnida.com and have a listen to audio on these | ||

| Subjects: Mujer (coming soon) Coyote (coming soon) American Revolution Interviews |

Seminars Archaeology History Recent History |

Oral History Poetry/Cuentos Música Comida DNA (coming soon) |

|

Please join the planning committee for the Nuestra Familia Unida podcast project at:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/podhi and help us organize as we attempt to find more information about our history and genealogy. Also to be notified when there is new content on the site join the very low traffic notification list: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/NuestraFamiliaUnida We need your help in finding audio related to our history and genealogy. If there is a Seminar, Lecture, Discussion, Info Session, or Organization Meeting that presents information related to our History or Genealogy please encourage having this information archived at the Nuestra Familia Unida podcast. If you know of a Historian, Genealogist, Professor, Story Teller, or Knowledgeable Individual that has a message that needs to be heard please contact us through the planning committee or through the contact information provided. Your help is much needed please consider lending us your support in this project. Joseph Puentes 206-339-4134 (messageonly) http://NuestraFamiliaUnida.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/podhi http://groups.yahoo.com/group/NuestraFamiliaUnida NFU@JosephPuentes.com > > > > Dialog of the Dead . . . Readers-Actors Needed for Play < < < < Needed: Actors, Readers, Interested Individuals. Author Historian Rubén Sálaz Márquez has given me permission to produce his play Dialog of the Dead. I'm been given limited permission to produce the play only for the Nuestra Familia Unida podcast. I'm looking for volunteers to read each part. If you have a good voice and can read well I would encourage you to read over the part you are interested in and lets start recording. http://www.historynothype.com/deaddialog.htm Parts available: Narrator (female), Chicano, Above-It-All, María (female), Latino, Immigrant (female), Hispano, Heckler, Policeman, Immigration Officer (female) Joseph Puentes, http://NuestraFamiliaUnida.com ps: Podcasting is just a little over one year old. There is much room for a wide variety of podcasts on many subjects related to our people. If you have a message that would benefit the community please contact me and we can work through the technology to get you up and running. The time is ripe. Never has there been an easier and low cost way to get your message out to the community. If you have something to say let's work together in saying it. |

| Excerpt: Adding Color to Red, White and Blue For '06 Winter Games, United States Fields Its Most Diverse Team By Amy Shipley Washington Post Staff Writer, Thursday, February 9, 2006; A01 Sent by Howard Shorr Additional information added from Hispanic Link Weekly report, Vol.

24.8, Feb 20, 2006. |

| Business | |

| Excerpt: The inexorable rise of Latino USA By Ros Davidson in Los Angeles, 22 January 2006 http://www.sundayherald.com/53697 Sent by Juan Ramos jramos.swkr@comcast.net Hasta la vista, older white America. Young Hispanics are the cutting edge. This coming October, America’s population will reach 300 million. The symbolic 300 millionth will probably be a Mexican-American baby in Los Angeles with bilingual siblings and parents who speak Spanish at home. The prediction of a landmark “Chicano” birth may not be exact, given the law of probability, but it’s the new American idiom – Latino, urban and multi-cultural – says Bill Frey, a demographer at the Brookings Institute, a think tank in Washington DC. “The new baby is symbolic of America’s 21st century,” he says. It’s the America of President George W Bush courting Hispanic votes; of singer-actor Jennifer Lopez and “reggaetón” music, a mix of Latin hip-hop, dancehall reggae and salsa that originated in Panama and Puerto Rico and swept the US last year. Los Angeles, the second largest city in the US and the template for its future, is half Latino. Last year LA elected a Latino leader, the first since 1872, not that long after California broke away from Mexico. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, popular, young and a rising political star, is being courted by Democratic bigwigs from Hillary Clinton to Howard Dean. Nationally, Latinos number only about 45 million, a population centered in California, New York and in Miami , where many street signs are in Spanish. But Hispanics are the fastest growing ethnic group and, since 2003, outnumber the black community. By about mid-century, for the first time in almost 300 years of American independence, whites will technically be a minority. For businesses and politicians, Hispanics are the new El Dorado. They may lack political and economic clout, but as a market they’re young and worth an estimated $363 billion. Next month, Toyota breaks new ground by airing a Spanish-English television advert during the Super Bowl coverage. The $1 million half-minute advert depicts a Latino father and son talking about a hybrid, forward-looking car – and about being a bilingual family. | |

|

And in March, Reebok will launch a Daddy Yankee trainer, named for the

Puerto Rican reggaetón star whose hit single Gasolina spearheaded the

breakthrough last year. Major chain stores such as Circuit City, JC

Penney,

Sears and Target recently added bilingual staff and Latin- oriented

product lines. Note this marketing item: El Valiente pictured in a lotteria card carrying a box of Huggies in one hand and a baby in need of a diaper change in the other. |

New Latina Voz on the Web By Rosalba Ruiz, The Orange County Register Sent by Sonya.Herrera-Wilson@xeroxlabs.com www.theLatinaVoz.com At a glance, Online news magazine targeted at U.S. Latinas that covers social, cultural and economic issues in English and Spanish. Subscriptions are free and readers can receive weekly summaries of news relevant to Latinas by e-mail. History on Publisher, Lorraine Quintanar: She and her five brothers were raised by their single mother. She credits the women in her family for her success. Studied political science in college and went on to work in the advertising industry for several years before taking a year off to travel through the United States, Canada and Europe. She also worked as a headhunter. Lorraine Quintanar's grandmothers used to tell her that she should give back to her community whenever possible. When she noticed a lack of coverage on issues affecting Latinas in the '04 election, she wanted to make a difference. In December, Quintanar launched the online magazine theLatinaVoz.com, a bilingual site featuring articles about social, cultural and economic issues targeting U.S. Latinas ages 25 to 45. "I believe we are the only bilingual online news magazine for Latinas," says Quintanar, 41, of Laguna Niguel. "Women are very busy, and the Internet is a quick way for them to stay informed." After conducting research that included women's focus groups and surveys, she opted to use the Internet as a vehicle for her publication. She found out that 59 percent of U.S. Hispanics used the Internet every month, compared to 68percent of non-Hispanics. She decided to target all Latinas, no matter their income or educational level, because "the idea behind LatinaVoz is to provide the information and resources to them so that they can improve the quality of their lives." |

|

Excerpt: For Hispanics, Farming is a Growth Industry Jenalia Moreno http://www.hispanicbusiness.com/news/newsbyid.asp?id=27651 January 21, 2006 At a time when many other farmers are giving up, Humberto Moctezuma dreams of increasing production on his cactus farm. "If the market demands it, I can grow with the market," Moctezuma, 48, said on a recent morning as he examined his crop, fertilized by chicken manure. He sells the cactus pads, nopales in Spanish, to mostly Hispanic customers who cook the vegetable, eating it with eggs, salads or meat. Moctezuma is one of a growing number of Hispanic farmers in the nation. Between 1997 and 2002, the number of Hispanic-run farms grew 51 percent. At the same time, the number of farms run by African-Americans and Anglos declined, according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service. Like Moctezuma, many Hispanic farmers are immigrants who picked up the skill in their home countries. Moctezuma's father and brother work a 130-acre cactus farm called Rancho El Periocolo in the Mexican state of Hidalgo, where Moctezuma was raised. For many Hispanic immigrants, owning land is a symbol of prestige, said Mario Delgado, a U.S. Department of Agriculture rural development specialist in Georgia, where he is helping to organize a March conference on Hispanic farm operators. "A lot of Latinos have their roots in the land," said Delgado, who added that Hispanic farmers rarely seek government subsidies and other assistance because they don't know about such programs or don't want to deal with more paperwork. "They really go for it with gusto." Some Anglo farmers are quitting the business because it's hard work that pays little. "There's just so many opportunities out there to do other things," said Kevin Kleb, who once raised mustard greens and eggplants in Klein. "You're trying to tie the greens in the cold and at $7 a pound, you think, 'What's the point?' " Many farmers no longer want to put up with the risks inherent to the profession, Kandel said. Fluctuating crop prices, droughts and pests plague small farmers who are increasingly competing with agribusinesses. "It presents an opportunity for people who are willing to incur those kinds of risks and the challenges of running a small farm," Kandel said. Moctezuma decided to take on those risks after years of importing produce from Mexico and facing slowdowns at the border. In 1989, he began his weekly ritual of driving his pickup truck laden with nopales from Hidalgo to the farmers market on Airline Drive near the 610 Loop. By then the farmers market had already become a meeting place for Hispanic vendors and their primarily Hispanic customers. It's a place where haggling over the price of tomatillos, tamarindos and Topo Chico carbonated beverages is done primarily in Spanish. Vendors sell produce raised in Mexico, California, Florida or the Rio Grande Valley, and little of it is grown in Harris County or the surrounding counties. "All that land is getting developed," said Kleb, who is now the manager of the Farmer's Marketing Association of Houston. "There's not much ag left in this area anymore." But back in 1942, when the market opened as a cooperative, it was supplied by local German, Italian and Japanese farmers. By the 1980s, Hispanic vendors and buyers began frequenting the market, and today 90 percent of the customers are Hispanic, Kleb said. And many of these customers are looking for products from their homelands. Mexico City native Reina Hernandez shopped for produce with her children as she sipped coconut juice out of a plastic baggie. El Salvador native Manuel Escobar and his sister drive from Huntsville every two weeks to buy chayote, pineapple and boxes of mangoes and other produce. "It's more fresh and a little cheaper," he said. For Moctezuma, the farmers market was an ideal place to sell his nopales. "It's a tradition for us" to eat nopales, said Elvira Torres, a native of Guanajuato, Mexico, who purchased more than six pounds of Moctezuma's nopales from the market one morning. Small farmers like Moctezuma are realizing that by growing such niche products, they can make a living. "I think that is increasingly the trend among a lot of small farms. They do a lot of gourmet products and a lot of expensive vegetables and specialty crops," Kandel said. "I would bet on nopales before I would bet on carrots." So far, Moctezuma, who believes the market for nopales is growing beyond Hispanics, has cactuses on just one acre of his 98-acre farm near the Big Thicket's Big Sandy Creek Unit. In two months, he plans to plant three more acres. And he envisions ultimately clearing away the tall pine trees that fill his property and replacing them with rows of cactuses and a patch of artichokes. "The American market is very anxious to try new things," Moctezuma said. | |

Excerpt: Some day laborers report being abused and cheated in their pay Researchers surprised by the pervasiveness of wage violations, dangers on job By Steven Greenhouse, New York Times (January 21, 2006) Sent by Howard Shorr howardshorr@msn.com The first nationwide study on day laborers has found that such workers are a nationwide phenomenon, with 117,600 people gathering at more than 500 hiring sites to look for work on a typical day. The survey found that three-fourths of day laborers are illegal immigrants and that more than half said employers had cheated them on wages in the previous two months. The professors who conducted the study said the most surprising finding was the pervasiveness of wage violations and dangerous conditions that day laborers face. "We were disturbed by the incredibly high incidence of wage violations," said study author Nik Theodore, of the University of Illinois at Chicago. "We also found a very high level of injuries." Forty-nine percent of those interviewed said that in the previous two months an employer had not paid them for one or more days' work. Forty-four percent said some employers did not give them any breaks during the workday while 28 percent said employers had insulted them. "This is a labor market that thrives on cheap wages and the fact that most of these workers are undocumented. They're in a situation where they're extremely vulnerable, and employers know that and take advantage of them," said another study author, Abel Valenzuela Jr., of the University of California at Los Angeles. The study said the number of day laborers has soared because of the surge of immigrants, the boom in homebuilding and renovation, the construction industry's growing use of temporary workers and the volatility of the job market. The biggest hope for day laborers, the study said, are the 63 day-labor centers that operate as hiring halls where workers and employers arrange to meet. These centers, usually created in partnerships with local government or community organizations, often require workers and employers to register, helping to reduce abuses. Many of the centers set a minimum wage, often $10 an hour, that employers must pay laborers. | |

| Get

Fuzzy Gold enduring Mystique California Gold Rush and the "49ers" The greatest theft in history Smithsonian and the Spirit of Ancient Colombian Gold Latinos in the Smithsonian Revised Targeted Minorities Fuss and feathers at the U. of I. |

|

The Orange County Register February 19, 2006 I love to read the daily cartoons, so it was a bit of a puzzlement to read the first frame of Get Fuzzy and a reference to aliens. |

|

|

| Gold

enduring Mystique Orange County Register, December 11, 2005 Below is example of the easy way that reference to Hispanics/Latinos and the history of the Spanish is included and maligned. The statement under the photo of the article by Robert J. Samuelson, syndicated columnist was published in extremely bold print, such as you see here. | |

|

|

|

| Brought up in California, I

was very aware of the "49ers" presented in school as types of

folk heroes, men and women fighting the elements, striving for a better

life, etc. etc.. However, that simplistic presentation of California

history in elementary school was totally erroneous. January 18, 1998, California State Historian Kevin Starr speaking of the California Gold Rush wrote "It was true that Americans indulged in an orgy of self-seeking. As a matter of social history, the legacy of the Gold Rush was obvious: Thousands upon thousands who otherwise would never have thought of migrating to America's remote Pacific territory poured into California, which in 1848, when gold was first discovered, had a non-Indian population of barely 18,000. Infinitely more tragic, the Gold Rush even further decimated the Indian population, whom the miners frequently cleared from their path like so many vermin. Indians not murdered were frequently enslaved, especially children and adolescents. Only one horrible word, genocide, can be employed accurately to describe the effects of the Gold Rush on Indians in the mining regions. Likewise were the Old Californians (Latinos in current parlance) pushed further to the wall, although they did manage, especially in Southern California, to hold on for another generation." | |

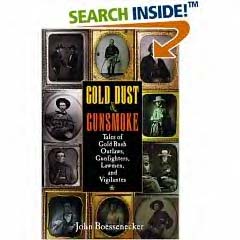

"One moment the

California creek beds glimmered with gold; the next, the same creeks ran red with the blood of men and women defending their claim or ceding their bags of gold dust to

bandits, "so writes John Boessenecker in his never-before-told tales of the American frontier,

Gold Dust and Gunsmoke . "One moment the

California creek beds glimmered with gold; the next, the same creeks ran red with the blood of men and women defending their claim or ceding their bags of gold dust to

bandits, "so writes John Boessenecker in his never-before-told tales of the American frontier,

Gold Dust and Gunsmoke .

"A lust for gold was the driving force behind the conflicts that developed as a diverse group of participants each fought for a share of the promised fortunes. Violence and lawlessness ran rampant in the 1850s, recording the

highest homicide rate in the history of peacetime US "

| |

|

The New York Herald printed news of the discovery in August 1848 and the rush for gold accelerated into a stampede. Gold seekers traveled overland across the mountains to California (30,000 assembled at launch points along the plains in the spring of 1849) or took the round-about sea routes: either to Panama or around Cape Horn and then up the Pacific coast to San Francisco. A census of San Francisco (then called Yerba Buena) in April 1847 reported the town consisted of 79 buildings including shanties, frames houses and adobes. By December 1849 the population had mushroomed to an estimated 100,000. The massive influx of fortune seekers Americanized the once Mexican province and assured its inclusion as a state in the union.

http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/californiagoldrush.htm | |

For

even more current history of gold lust and inhumanity, the example

would be Nazi brutality during World War II. With no regard for

humanity, the Nazi got gold - mounds of gold, from the gold fillings taken out of the mouths of Jewish

victims. Searching the web for photos and

information was easy. The headlines on a Dec 1, 1997 BBC

article read: World: Analysis, The

greatest theft in history went on to describe Germany's action

as:. For

even more current history of gold lust and inhumanity, the example

would be Nazi brutality during World War II. With no regard for

humanity, the Nazi got gold - mounds of gold, from the gold fillings taken out of the mouths of Jewish

victims. Searching the web for photos and

information was easy. The headlines on a Dec 1, 1997 BBC

article read: World: Analysis, The

greatest theft in history went on to describe Germany's action

as:. | |

| It was one of the greatest thefts by a government in history; the confiscation by Nazi Germany of around $580 million of central bank gold -- worth around $5.6 billion at today's prices. The gold came from governments and civilians, including Jews murdered in concentration camps, from whom everything was taken down to the gold fillings of their teeth. | |

Yet, with two major relatively recent historical incidents of greed, the unchecked anti-Spanish colonials sentiments continue. New March 2006 issue, Smithsonian, page 42, next to a gold Funerary Mask, 100 B.C. to A.D. 800 "The Spirit of Ancient Colombian Gold" show . . says HURRY IN . . . Spanish explorers would have killed (and did) for a

collection of Colombian gold as large as the one on view at the National

Museum of Natural History through April. These debasing comments appear frequently in the media, reinforcing negative attitudes towards the early Spanish colonizers. It supposes that either descendants of the Spanish colonists do not exist, or because of the accuracy of their comments that we do not take a stand in defense of our ancestors. Notice too in those quotes, one refers to the Spanish as

conquistadors and the other as explorers, The problem persists because incorrect history has

shaped a very negative perspective towards the role played by the

Spanish in the American continent. The Smithsonian is suppose to reflect

the discoveries and achievements of America, but the Hispanic/Latino is

still not an acceptable part of the vision. Our story has not been

told because we are telling it in the right places and to the right

people. In 1997, a 5-year report on the the Hispanic

presence in the Smithsonian revealed that in 1996 Latinos were 3.1% of the

Smithsonian staff.* |

|||||

| White African American |

59.6% 32.6% |

Asian

American Latino |

3.7% 3.1% < |

||

The 3.1% represents 167 Latino employees; however, only 3 were in a Senior positions. Out of the approximately 5,387 Smithsonian employees, only 3 Latinos hold Senior positions. Source: Smithsonian Workforce Profile through 3/97; Bradley and Paulino, "Latinos in the Smithsonian Revised"; U.S. Office of Personnel Management, Office of Diversity. *In the 1997 study the American Indian were only 1.0% of Smithsonian. However, since that study, the beautiful Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian is in Washington, D.C.. www.nmai.si.edu January 2006, a Black History Museum approved for construction by the Smithsonian, Click

We need Hispanic/Latinos on the staff of museums, historical

sites, in national parks, concert halls, performing arts centers, PBS and

educational channels. Most agencies, public or private reach out with

internship programs. For more information about research and

scholarship at the Getty in California, go to www.getty.edu/research |

|||||

|

Targeted Minorities By Rubén Sálaz Marquez author of the EPIC OF THE GREATER SOUTHWEST, Click for more information saljustin@msn.com In 1972 a group known as the “Concerned Alumni of Princeton” was formed to combat entry of women, blacks, and Hispanics to this Ivy League university. This effort was not publicized, of course, so that “women, blacks, and Hispanics” would never consciously realize they were being prevented from attending Princeton by “Concerned Alumni.” This way rejected prospective students would likely blame themselves instead of nefarious societal forces like the “Concerned Alumni.” History has shown that Californios, Tucsonenses, Hispanos, and Tejanos have generally been hospitable, kind hearted people. Most people don’t wish to believe that they are being targeted for exclusion from Princeton (or Stanford or Ohio State or how many other schools or universities that we can’t prove?) but this small slice of history demonstrates what forces are working against anyone designated as a “minority” in the USA. The idealism of the Declaration of Independence must be weighed and considered along with the realities of the Dred Scott Decision. This is crucial for anyone who is a member of a targeted group, minority or otherwise. If we don’t recognize American realities we are doomed to suffer from them and worse, pass the sufferings on to our children and grandchildren. One way to become more aware of what is really going on is to read widely in the field of history. While American historiography is laced with propaganda, if one reads widely enough you will have a good chance of recognizing fact from fiction, analysis from cultural bias, valid history from mere propaganda. Without a strong background in history the ordinary person is intellectually defenseless. You can be told anything and you have no way of knowing if it is true or false. For example, the missions and missionaries of California have been denigrated beyond belief only because most people don’t know much about mission history so just about any assertion can be made without serious contradiction. The same thing has happened to Juan de Oñate in New Mexico. Many people in the Southwest are passionate about genealogy. The next step, after identifying one’s ancestors, is to study how our people actually made their personal history. Most Southwesterners will be very proud of those ancestors once you discover how they really lived. But leave history to forces like the “Concerned Alumni” and you and yours will be viewed as unworthy, if not vile. Is this being sort of paranoid? Read widely in history and decide for yourself.

|

|

Fuss and feathers at the U. of I. By George Will Orange County Register, January 5, 2006 The University of Illinois must soon decide whether, and if so how, to fight an exceedingly silly edict from the NCAA. That organization's primary function is to require college athletics to be no more crassly exploitative and commercial than is absolutely necessary. But now the NCAA is going to police cultural sensitivity, as it understands that. Hence the decision to declare Chief Illiniwek ''hostile and abusive'' to Native Americans. The Chief must go, as must the university's logo of a Native American in feathered headdress. Otherwise the NCAA will not allow the university to host any postseason tournaments or events. This story of progress, as progressives understand that, began during halftime of a football game in 1926, when an undergraduate studying Indian culture performed a dance dressed as a chief. Since then, a student has always served as Chief Illiniwek, who has become the symbol of the university that serves a state named after the Illini confederation of about a half-dozen tribes that were virtually annihilated in the 1760s by rival tribes. In 1930, the student then portraying Chief Illiniwek traveled to South Dakota to receive authentic raiment from the Oglala Sioux. In 1967 and 1982, representatives of the Sioux, who had not yet discovered that they were supposed to feel abused, came to the Champaign-Urbana campus to augment the outfits Chief Illiniwek wears at football and basketball games. But grievance groups have multiplied, seeking reparations for historic wrongs, and regulations to assuage current injuries inflicted by ''insensitivity.'' One of America's booming businesses is the indignation industry that manufactures the synthetic outrage needed to fuel identity politics. The NCAA is allowing Florida State University and the University of Utah to continue calling their teams Seminoles and Utes, respectively, because those two tribes approve of the tradition. The Saginaw Chippewa tribe denounces any ''outside entity'' -- that would be you, NCAA -- that would disrupt the tribe's ''rich relationship'' with Central Michigan University and its teams, the Chippewas. The University of North Carolina at Pembroke can continue calling its teams the Braves. Bravery is a virtue, so perhaps the 21 percent of the school's students who are Native Americans consider the name a compliment. The University of North Dakota Fighting Sioux may have to find another nickname because the various Sioux tribes cannot agree about whether they are insulted. But the only remnant of the Illini confederation, the Peoria tribe, is now in Oklahoma. Under its chief, John Froman, the tribe is too busy running a casino and golf course to care about Chief Illiniwek. The NCAA ethicists probably reason that the Chief must go because no portion of the Illini confederation remains to defend him. Or to be offended by him, but never mind that, or this: In 1995, the Office of Civil Rights in President Clinton's Education Department, a nest of sensitivity-mongers, rejected the claim that the Chief and the name Fighting Illini created for anyone a ''hostile environment'' on campus. In 2002, Sports Illustrated published a poll of 352 Native Americans, 217 living on reservations, 134 living off. Eighty-one percent said high school and college teams should not stop using Indian nicknames. But in any case, why should anyone's disapproval of a nickname doom it? When, in the multiplication of entitlements, did we produce an entitlement for everyone to go through life without being annoyed by anything, even a team's nickname? If some Irish or Scots were to take offense at Notre Dame's Fighting Irish or the Fighting Scots of Monmouth College, what rule of morality would require the rest of us to care? Civilization depends on, and civility often requires, the willingness to say, ''What you are doing is none of my business'' and ''What I am doing is none of your business.'' But this is an age when being an offended busybody is considered evidence of advanced thinking and an exquisite sensibility. So, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals has demanded that the University of South Carolina's teams not be called Gamecocks because cock fighting is cruel. It also is illegal in South Carolina. In 1972, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst replaced the nickname Redmen with Minutemen. White men carrying guns? If some advanced thinkers are made miserable by this, will the NCAA's censors offer relief? Scottsdale Community College in Arizona was wise to adopt the nickname ''Fighting Artichokes.'' There is no grievance group representing the lacerated feelings of artichokes. Yet. |

| Guy

Gabaldon Documentary Finally Completed Texas Vietnam Veterans |

|

|

Honolulu Star-Bulletin Hawaii News | |